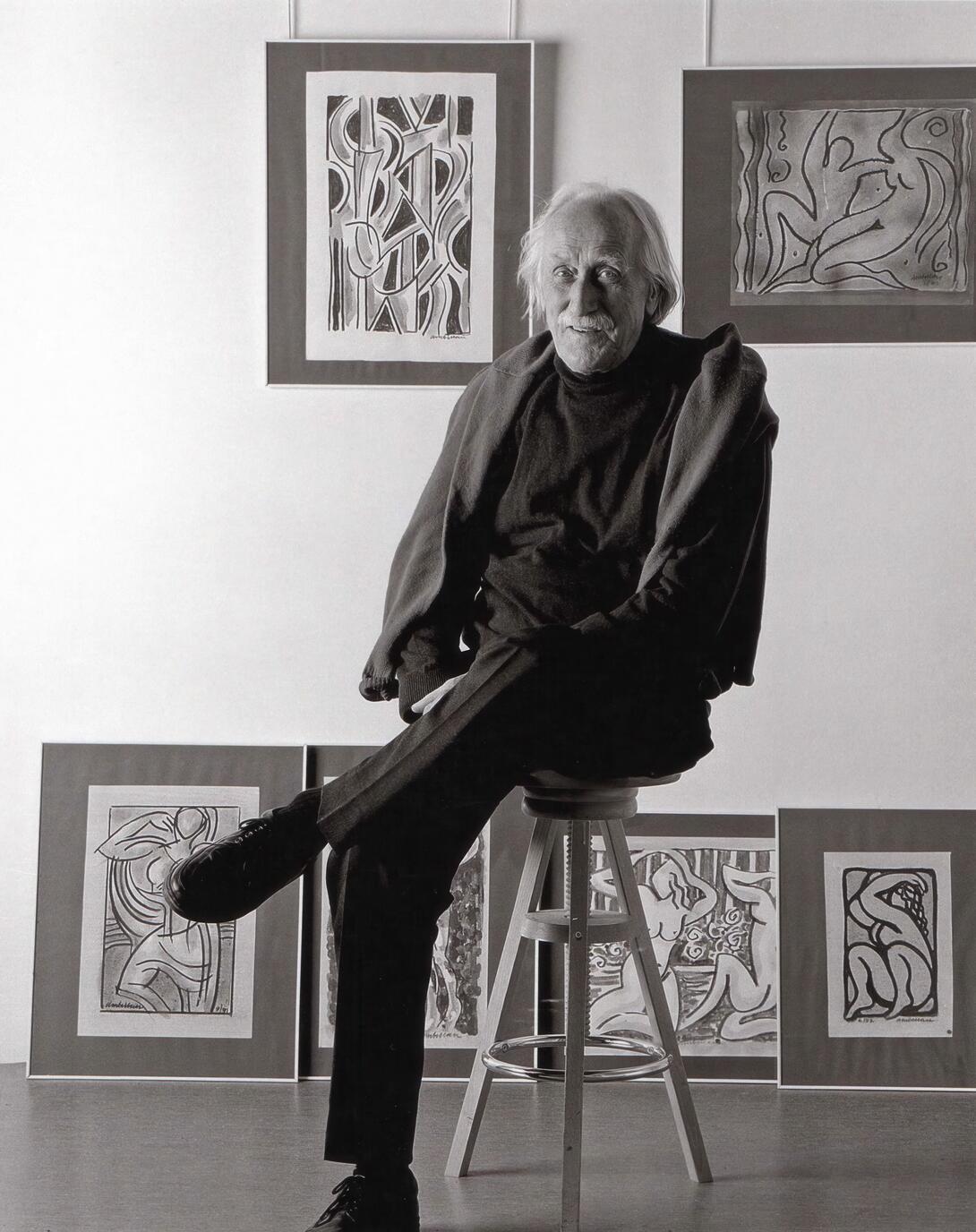

Born in 1912 in Buffalo, New York, Harold Ambellan belonged to the American generation between the two world wars. He studied sculpture and fine arts in his hometown while the economic crisis of 1929 shook the United States.

In 1930, left Buffalo to settle in New York and obtained a scholarship to the Art Student League, where he studied for two years. At that time, the Roosevelt administration implemented a vast employment plan in the wake of the economic crisis. Artists joined forces and requested to participate in this plan. Their request was granted, and thus the Federal Art Project was born. This project, set up by the federal government, provided subsidies to artists in exchange for public commissions. This led to the most flourishing production of works of art ever seen in the United States, in all artistic fields: visual arts, dance, theater, music...

Surrounded by artist friends such as Willem De Kooning, Isamu Nogushi, Martha Graham, Walter Evans, Woody Guthrie, and Siqueiros, Ambellan's sculpture was influenced by German Expressionists, artists such as Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Derain, and William Blake, as well as classical Greek art, Indian art, and African art.

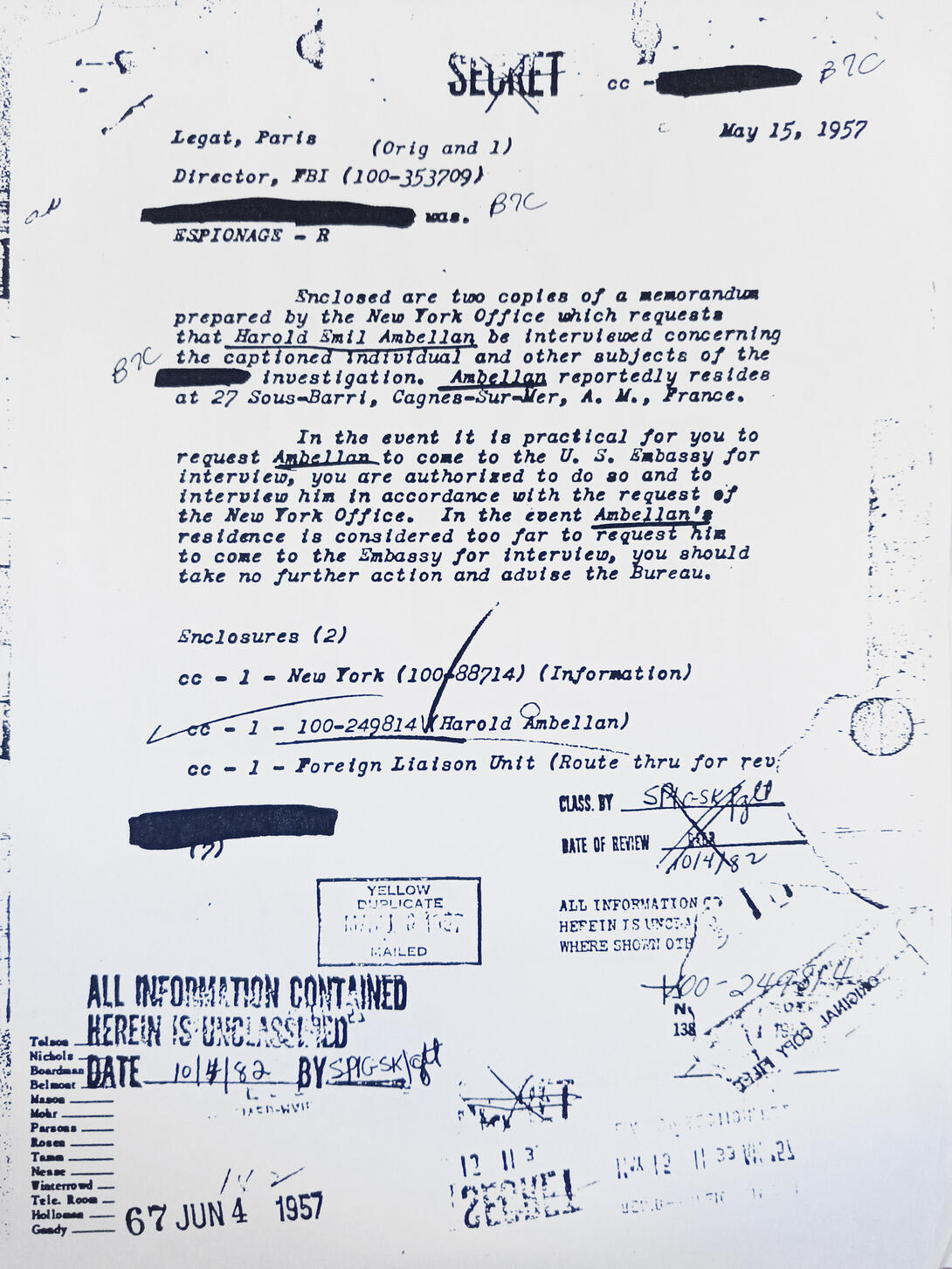

As a member of a committee welcoming refugee artists, he also befriended European artists (Lipchitz, Zadkine, etc.). His political views, too left-wing for McCarthyist America, forced him into exile in France in 1954.

Chapter 1... Buffalo youth

I was born in Buffalo in 1912. It was the year the Titanic sank. I was too young to worry about that. I grew up in Buffalo, which was a wonderful place to grow up. It was a city not too large and not too small. We could walk from our house to the downtown area in 20 minutes and it was a pleasant walk. Buffalo was, and still is, a mixture of many immigration periods in America.

There was a large German section with a German newspaper, a Polish sector with a Polish newspaper and a large English-speaking quarter with two other newspapers.

I was born in the neighbourhood with an easy access to the town center and also very close to the edge of the town. In five minutes, I would be in an area that was neither country, nor city, but open neglected fields with streets outlined, waiting for construction and population and while I was young that whole area was being built up. Still, a circus ground remained and every year we would get” the greatest show on earth”. The Barnum and Bailey Circus came to town – truly a marvellous event.

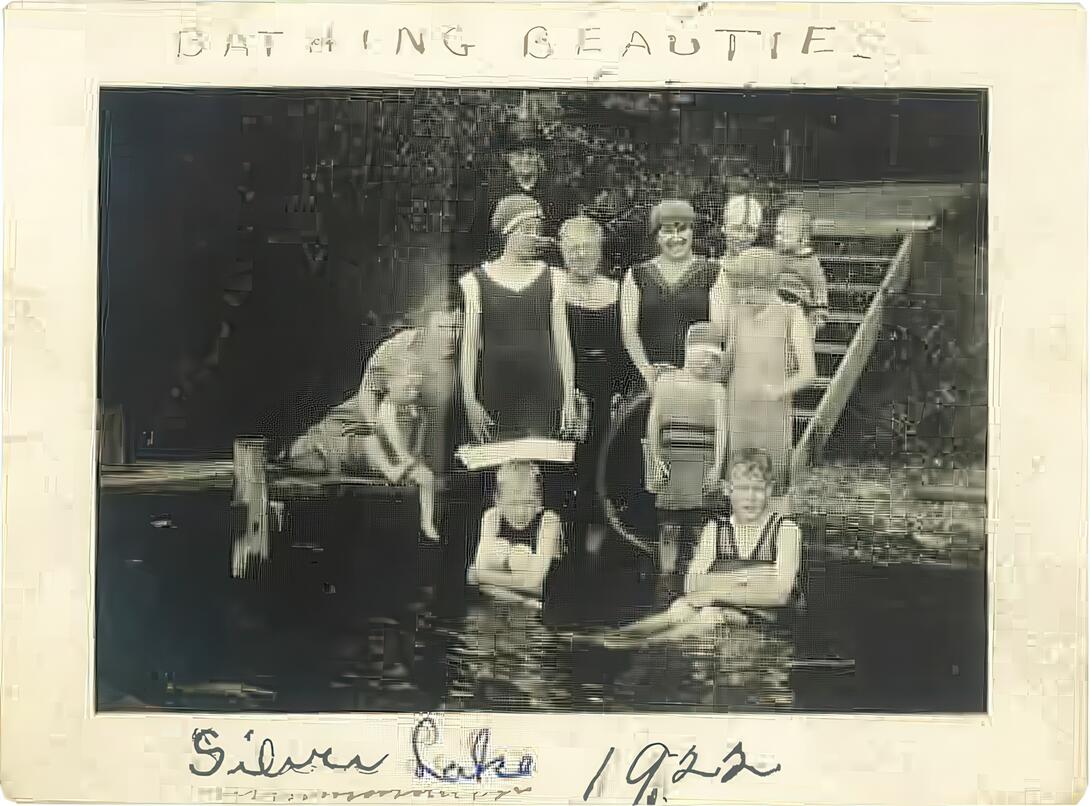

As I grew older, in my teens, I wandered further on my bicycle with friends. The charm of Buffalo is that it is on Lake Erie at the beginning of the Erie Canal which is connected with Niagara falls. In Buffalo there was a ferry boat across that river to Canada. Imagine living in a city on the edge of two countries and I was able to cross to another country for 5 pennies on a ferry boat! There was no question of passports; just as freely as you wished, you could go to Canada and come back. The ferry boat took you to Fort Erie, a little town nearby and to the beach. There was a little train with a locomotive, a replica of a big one. Everything was reduced to a pleasant miniature size and that train took us to Fort Erie which was the bathing beach and pleasure center for Buffalo.

This Erie beach had merry-go-rounds, with a carousel, a modest thing that costed pennies. I remember there was a building with a long stairway going up to a slide going down and you entered there and they gave you a piece of carpet. You sat on the floor and descended several bumps. You were able to repeat that as often as you wished and the cost was 5 cents. Five cents was a magic amount of money. It’s amazing the value of money. During my youth and till I left Buffalo, it was almost unchanged. It remained about the same and it’s hard to believe that money could have been so steady and reliable, but it was.

With my bicycle, I went to the surrounding countryside. Just outside of Buffalo, there was an area where they grew cherries. It was called “Cherry Valley” and there were charming towns and they grew other things besides cherries. My house was built when I was one year old. We moved from German Street where I was born to Winslow Avenue and my father bought an empty lot and started making our house with contractors and workmen doing the work. We lived, during the time our house was constructed, in an apartment in the house next door and we were able to see our house being built very closely.

So we eventually moved into it. It was a very nice little house and is still standing, I do believe. Our house was very convenient for children because we were a city block away from the school, public school number 53, a red brick establishment which had a great deal of charm for me. My mother was very close to the school, because she had dreamt as a youth of being a teacher but she stopped going to school and her dreams of becoming a school teacher were abolished.

She took a great interest in our education and became a very good friend for the rest of her lifewith the school principal, a marvellous woman. My mother was very gifted but unfortunately she died very young during World War II. Luckily, at that time I was still in the States and I was able to come to Buffalo to visit her with my brother Fred before she died. I spent many afternoons with her and she was very heroic and very full of life until the very end. She died too young. She died of cancer in her 50s.

Of course, in my youth, I didn’t appreciate all those qualities but I recognize them now. When she wanted to emphasize something she wished to do, she adopted the name of an American Indian woman, Weptinoma, who was a chief of a tribe near Buffalo At a certain point, she would say very quietly: “Weptinoma has spoken.” Charming. My father was a painter and paper hanger and he had had an accident when he was younger.

He was working in a wholesale food establishment where there was a chute that went from the first floor building to the main floor. This chute was stopped during the day to make more space to move below and one day it fell on my father and broke his back. He was a long time recovering and after he was always subject to pain. There was no working insurance in those days and the thing you would expect when you had an accident in a company was to be fired.

No questions asked. My father was sometimes for weeks and sometimes for months incapable of working.

My brother Fred was just three years older than me, old enough to be physically stronger. He was fond of teasing me and playing practical jokes on me. He treated me like a servant. But I was much smaller than him (my period of growth was very late) and my brother took advantage of being stronger. He was also a serious student and I was never a model student.

My younger brother Charles was 6 years younger than me and he was a charming baby, full of life and laughter and joy, very expressive. Between my brother and an uncle of mine, we would toss that child in the air, like a ball and he would laugh. I didn’t have much contact with him as I grew up, I had my life and I really picked up with him when I was an adult, and he was a budding aviator. He was a pilot in World War II. It happened that all three brothers enlisted in

the US Navy. My father was an early driver of an automobile, the first car of our neighbourhood, a model T Ford and we were very proud of it. With this car we would go camping in the Adirondacks.

Camping at that time was a very, very dangerous idea: to go in the woods where there might be wild robbers and God knows what. So people threw up their hands when we were starting and we left with our tent with much stuff packed on that little car. We went to the Adirondacks and camped on the shore of Lake George, a big lake, and my father fished every day and we rented a canoe and Fred and I explored the lake and its little bays. Really very beautiful.

I was probably 6 or 7 when he bought the car. My grandmother was not living with us at that time but she came when I was 8. She had nine children, all boys except the first one. My father was the last son. She was at that time living in her daughter’s house who had wisely married a good man who died and left her very well insured. She became a very solid “bourgeois” and kept the mother in the kitchen. When my grandmother was 80 she finally complained to my father and his brothers, and started living in our house. It meant extra work for him and the responsibility of one more person to feed… So my father got a lot of respect from his mother but no help. She spoke English very well…

My grandparents came to America with all their children in 1859 or 1860 when America was in the middle of a Civil War. My grandmother and grandfather supported the antislavery movement and had a great affection for Abraham Lincoln. Her husband, my grandfather, was a mason, a house builder. They had a house with a stable, a workshop and storeroom right in the center of town.

My grandmother was a remarkable woman. She could see with only one eye but it didn’t prevent her from reading two newspapers a day. She read the English and the German newspapers and she read them down to the last lines. She knew everything that was going on. She lived to be 97.

Buffalo was settled mostly by Germans so the largest newspaper was in German. The second one was in English and later both were supplanted by the Polish newspaper. Poles after World War I came in great numbers and settled in Buffalo and cities around the great lakes.

My mother’s family had come over to America for different reasons: they chose to participate in what they thought would be the marvel of the world, a free country. They became a very important family in Buffalo and my grandmother married a man in the wholesale liquor business: wine and whiskies. He died early, leaving her with a rather nice house but also five charming children to bring up all by herself. She was very nicely helped by her brothers and sisters but her house burned down to the ground. Her house, adequate for her family of five children, was her only jewel. Then she was forced to move in a smaller, more compact house, easier to take care of.

One of the most “marriageable” members of the family when I was growing up was Dr Henry Frederick. He came to our house very often. He liked my mother very much, they had much in common. He stopped there often on his patients-rounds. He was supported in his medical career by his family. He practiced in his own way, often not charging his patients and never refusing anybody. He was a sort of a doctor of the poor with a good humour and a joy of living which was amazing. It was a pleasure to see him for a few minutes in the house and we were sure to laugh and be happy when he was around. A very charming man. Later, much later, my mother’s oldest sister married a Dutchman and had children. Her son Leroy became a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church. He was very not at ease with the hierarchy; the Dutch Church was very select and well founded on strict lines of lineage and legion to the earliest pure Dutch religious tradition. He was obviously difficult to place in this category because he had such a sense of humour, he couldn’t take anything seriously, including himself. They appointed him as a church official in Brooklyn, New York, which was an early Dutch settlement. But they soon found out that he was too adventurous for their religious needs. He established a summer program for youth and they found out that he not only welcomed the youth of the Dutch Reformed Church but all the youth of the neighbourhood including several races and colours.

It was more than the Dutch had bargained for and they sent him out to a very small and charming town as a minister. For many years, they never let him escape to larger areas but he became a champion of all kinds of legislation that favoured poor coloured migrants. He was noted in Albany, the state capital of New York, as someone who stood up for the poor.One day, at a family celebration, he said: “We have a doctor in this family and it is very pleasant to know that you can be well for nothing and you have a minister in this family which means you can be good for nothing!”

Chapter 2... Childhood, work

This idea of writing a biography at once attracted me but with a little reluctance. In fact the whole idea of making a book or writing anything is a little dubious to me. It involves the ego of thinking that you are going to be read by people. And that people are going to buy your words that have been printed and occupy themselves maybe for a week or two weeks dipping into your book in their spare time. I’m a little dubious about literature in that way. It has to be very great literature in order to exist for me. We can’t all be Cervantes or Shakespeare.

I was a sensitive and very timid child to begin with and I think that this shyness is a kind of egoism in reverse and really you take yourself very seriously. I was timid at school. I wanted to please the teachers and do my part and be a good pupil. Sometimes I failed and sometimes I succeeded; if I sort of liked the subject, I succeeded. And if I hated it, like I hated mathematics, I had very great difficulty passing the minimum tests. In fact I remember taking algebra and my mother saw I was suffering so with this. I was trying to cram for an examination. I thought: “My God, if I don’t pass this, I have to pass the whole year again. I’ll quit school and go on the bum. I can’t face that”. So my mother took my book and studied it well enough to help me to calm down and get enough algebra in me to pass that exam. I think that’s a wonderful story of a mother and describes my mother very well. She could do anything, she could build a house if she wanted to. She was a beset woman too because she had a husband who had had a bad accident in his youth and was partly paralysed in his back, in his movements, in his spinal movements and he was often laid up. She got a job at the local grammar school which was only a very short distance from our house, as a cook in the cafeteria. And that we lived on very much of the time of my youth. She loved it because she loved the school. Her dream as a young girl was to become a kindergarten teacher.

I was talking about my mother and I was not appreciative enough of my mother when I was a child but I certainly thought she was a marvellous person when I grew up to be a little bit older. As I say, she could do anything. And she became friend of the Principal of the school. Her name was Mrs James. She was a cousin of William James and Henry James. A marvellous person too and she loved my mother. She told me later: “Your mother is the most wonderful person I have ever met”. At any rate I get very sentimental talking about my mother. In her later years, she became the local organiser of the Parent Teachers Association and one of its founders in the State of New York. So she was still partly working as a cook and being a lady organiser of a going movement and sometimes going off to the State capital, Albany on behalf of the organisation. It’s hard to believe this simple looking woman was capable of such diversity and change. Our family was poor, so I always worked when I was a child, like being a delivery boy for a local bread store. There was a horse driven bakery who sent wagons around and I had the job of hopping around from the bakery wagon to people’s houses to bring them bread, pastry, rolls, or doughnuts. There, I worked for the driver of that wagon. The fellow I was helping was really an alcoholic. So he gave me the wagon and let me do the rest of the route every day, which was about twenty or thirty houses. I’d come round this big area, come back, pick him up at the bar and help him into the wagon. We’d count the cash and I’d put it in a secret place in the back of a drawer. He would climb in the wagon and fall asleep and so I would just close the half door of the wagon and say to the horse: “Alright Roany, you can go back to the stable now”. And Roany would understand and he’d go off. And for fun I said ‘good-bye’, like that, and I got in the wagon to see how he did.... And he’d come to an intersection, stop, go very slowly forwards, look both ways and cross. If the traffic was stopped, he waited; he was a very intelligent beast. He was called Roany because he was a certain colour called roan. I don’t know what that meant really.

I did a lot of different things. I did a lot of gardening as a young kid. In this lower bourgeois or working class neighbourhood, hedges were very important. A lot of people had hedges around their front lawn. And hedges involved trimming and I was an expert, hair trimmer, a barber of hedges. I did it for three elderly women, three elderly sisters. I was their gardener for dirty work. I came in now and then in summer time and spring time. They had very nice garden tools and I had the key.

I had the right to come any time, take any of those tools and use them wherever I went. So I had quite a nice batch of tools and I’d trim hedges. And because I was a kid and hedges attract all kind of rubbish and dirt, I’d get down on my hands and knees and clean them. It was good for you. I thought that was very good, how working class kids would work in those days at any rate. You get the habit of working and you like working all your life. If you get to do things, it’s a pleasure to do even a simple, stupid job and do it well. I think I developed the habit of liking to accomplish tasks and I think that carries over in all activity except the things that you don’t like.

Chapter 3… First signs of interest in art

The following is an attempt to trace, over the many years that have passed the first signs of interest in art in my childhood. Some of the incidents are very close but I can’t very well separate them into the age limitations. In other words, I seem to be always the same age whether I remember things in my early childhood or my school years... There are some things I’d like to explain in writing about myself or in talking about myself concerning the given idea of the development of an artist or the development of the art motivation in a child or young person and the reasons for becoming an artist and the process of entangling oneself with this craft.

At any rate, the first thing that comes to my mind in looking for my artistic evaluation is that my father decided at a certain point to build a garage at the back of our house and this entailed digging an area for the cement driveway to be installed, which led from the street. In the process of digging that soil, I uncovered a large streak of pure yellow clay that was immediately in a condition to be rolled into balls. So, with a trowel or little shovel, I got out as much of this clay as I could and filled a couple of buckets. I immediately started playing with it, rolling it and making objects with it. I know I made some animals and I made some figures of people, of children. All these things disappeared and all I have now is the feeling of pleasure in learning what you could do with clay.

I bought clay at a much later time, as an adolescent of perhaps fifteen, sixteen years. I remember I had some clay and I made several masks and heads and portraits of imaginary characters. This culminated in a bust, of Greta Garbo. I saw a photograph of her that stimulated me, I believed she was the most beautiful personality in the world and it was my pleasure and duty to translate her into a clay image so I did it. It was about quarter life size and it was with the head thrown back looking up at the sky. Greta Garbo, meticulously modelled and scratched and scraped.... Finally everybody saw it. My parents, my brothers saw it and people were impressed by this effort of mine. And I learned how to make a cast in plaster and I made a mould in plaster and then filled the mould with plaster with a separation of soap in the surface of the mould and made a positive of plaster of it, which exists somewhere. Later on, my brother asked me whether he could have it in his house and I said: “Yes, you may”. I don’t know what happened to it. At any rate, that was my first sculpture. At the same time, I made little drawings but I wasn’t motivated by paper, canvas, crayons or brushes. I liked real form, three dimensional positive forms. Later on, my interest in art led me to join all sorts of painting clubs. I remember going out and actually trying to paint landscapes with a group of people. I discovered that was not what I wanted to do. The idea of copying landscape of trees, fields and earth was too boring for me. It was nothing I wanted to do at any rate. It was also taught by someone who was very academically minded. There was only one way to do it and he tried to inculcate his point of view. That was one thing. As a child I would go to the Natural History Museum, a short walk from my house. There, together with a group, we would paint and draw objects coming from American Indian, Aztec and Southern American cultures. That was a very interesting and very pleasing experience. As I grew a little older, I went to Albright Art School. It was an art school adjoining to the Albright Museum. The Art school gave life drawing free classes to people who passed an elementary admission examination to see whether they were serious or not. So I was chosen as a candidate for that school and I went two nights a week for several years to that art class. There was a model there, who was a very strong man who worked in a circus in summer and in the winter, he posed for this class, among other things I suppose. He was charming because he told very nice stories about his experiences in the circus and in theatres and so on. In the evening, in the rest room, in between poses, he had a rubber strap that you could extend and you could pull it round your back and push it forward and do all sorts of exercises with it He showed us how strong he was by pushing this thing out, and giving it to us to try. So one day he had that thing he had already shown us and he had a whole group of us looking at him and listening to his story. He put this strap behind his head and pulled the two ends of it forward and trapped his head stiff with his neck. So he got the thing out very far and then he dipped his head and the rubber slipped off the top of his head and carried off his wig. We had not known that he had a toupee on. Then, he simply walked across the room and found the toupee and made as if to spit inside it and flattened it on his head. It was all a premeditated act. It was beautiful to see the modesty of a man making a fool of himself in order to amuse his friends. Even at an early age, I discovered why I was interested in art. The desire to conform to a certain pattern on the part of the people of that period was general. They approved of everything that society dictated. Art was the only activity that could possibly be a personal choice to rebuke the deadly conformism. In other words, I came to believe and still believe that chief artistic motivation is criticism of certain aspects of society. In the way the artist or writer or dramatist or musician even decides that he will try to win people over to a new interpretation or a new point of view or a conflicting point of view to the popular one. I still believe that art begins with this “negative” criticism of conformist ideas.

Until the age of fifteen, I lived in a country which was very prosperous and where everyone who wanted to work, found a job or a profession or trade that allowed him to live and raise a family.But when I was fifteen or sixteen the Great Depression hit America. By the time I graduated from High School, jobs were extremely hard to find. I graduated in 1930 at the age of 18. I remember looking for work very assiduously. My brother Fred on the other hand had begun college and a very affordable college because it was a teachers college and it was free. It was a State Teachers College. He became a teacher for life.

I looked for work in the daytime and went to Art School in the evenings. But my parents bemoaned the fact I was interested in art because even if there was any job it was not for an artist or an art student. I remember going on long lines for companies that advertised for a certain position and the lines were sometimes seventy people standing in line for one very low paid job.

I finally got a job as a male clerk in a life insurance company in Buffalo New York. It was nothing that I liked very much but it was very simple. I had to collect letters. I was sort of an interior postman. I had to buy stamps, stamp the letters and see that they were properly addressed and deposit them in the mail box. Also I had to file correspondence in a battery of filing cabinets. My family was very contented and I brought home a little money to help out. Everybody was very happy except it was a very boring job. The only thing that relieved the boredom was that there were one or two people that I liked among the staff, a girl by the name of Edna and a young boy by the name of Tom who later took my place.

I continued that job for about a year. Then somebody moved out, died or quit or I forget what.

There was a movement of everybody going up one step in the hierarchy. So I was promoted from a mail clerk to a counter clerk at the counter where people with insurance would come in with their problems. And hell, I had enough problem... It involved figuring out premiums or whether this was right or that was right or whether it was more advantageous to do this or that. The chief of that office, who hired me in the first place, called me to his desk. His desk was right in the middle of the office. He said, “I hate to do this but you are not happy and you are not going to be happy in this work ever, because you are not made for this kind of a job”. He said: “I will keep you on for three months anyway but start to look around for another job. Don’t worry and if you need to go out and interview with people I will understand that”.

He gave me a three month period in which to find something else. He was very, very kind and very nice and I could see that he just had to replace me with somebody who belonged to the world of insurance. Before the three months were up, I found another job in a large department store as a stock boy in the books and stationary department. That meant opening cases of books and stationary and sorting them out and bringing them from the dark basement up to the stores and placing them in their proper place on the shelving. This was not a very wonderful job, 16 dollars a week, I think, which was bare subsistence. I don’t know how that ended but then I got a job in a Cut Price department store on the same main street in Buffalo. I was hired just before the Easter season to unpack and bring the chocolate Easter bunnies in from the warehouse to the shop, as needed. They were made in an adjacent room in the warehouse by a man who earned his living by filling tin moulds with chocolate and rotating them to get a film of chocolate on the inside. He made many rabbits and eggs which he somehow decorated with warm chocolate that came out of a tube. You could even write names and Happy this and that. The Easter season passed and there was nothing for me to do in that department anymore. So they transferred me to the furniture section where they needed someone to help.

I was assigned to help this elderly, dignified man who was an excellent artisan in wood. I was mostly sandpapering, varnishing, staining and waxing counters and showcases and putting glass in windows. It was interesting, pleasant work and a very charming boss taught me lots of little tricks of the trade. He spoke very well of me to the boss, Mr. Wolfson, who sent me to his house to fix some windows that were stuck and do some little repairs in his rather bourgeois house; not really a mansion but a respectable house on the parkway.

And so I did that, and he also trusted me with his wife, who was very, very nice to me. A very charming and nice woman, not at all my dream girl, but a very nice person. So I did these things and he couldn’t praise me enough. He was happy with me. He came when I was just leaving, when

I was just finishing for the day. And he told me what a fine workman I was, repairing those things so quickly and so well: guillotine windows where the sash finally breaks and has to be replaced and all kind of little problems like strange legs on chairs and so on. He treated me as a young man, a friend. When I finished the house, I worked for a while more in the store in the same department and Mr Wolfson one day called me into the office and said: “You know you are late this morning”. They had a time clock. “You are sixteen minutes late.” I said: “I know I am late because the street car didn’t come along. I found there was an accident on the street car line so I had to walk the rest of the way. You can call the street car company and ask them”. He said: “I told you, I tell everybody I hire: if you are late three times you are out. I can’t make an exception for you, Harold”. So he fired me. To fire me, he had me in his office where his desk was on a slight platform to bring him higher than the person he was addressing. So he fired me in glory from his platform and he said: “It’s with great regret that I do this” and such nonsense. So I said: “Don’t worry about it, I’m very glad to get out of this place, don’t worry… It’s nothing much of a job, you know”. At any rate, Mr. Wolfson won. The boss always wins. My mother felt guilty that I had to work at these jobs instead of going to art school. So, she enrolled me without asking me in a mail order art course found in the newspaper or magazine which of course was commercial art. They sent a folding drawing table, some primary colours and measuring instruments, rulers, compasses and pencils. I was supposed to follow a course of lettering and anatomy and tricks of light and shade and so on. I quickly gave that up. I didn’t want to tell my mother that she had made such a stupid buy and finally I did use that table. It was quite ingenious; a very solid drawing board that fitted at a slant which was variable. It was a very good thing. I wish I had one like that.

The Depression had already set in. Mr Hoover was defeated and Mr Roosevelt was elected. Mr Roosevelt commenced by taking very sweeping decisions, protecting labour and taxing industry. One of the ways in which he solved the problem of unemployment was to make schools for all different trades and projects that fitted in with these schools. It became finally the Works Project Administration, WPA, which covered the whole nation. It built and furnished schools, hospitals, homes and bridges and necessary roads, forestry control, rebuilding the American wealth which is within these things. So he was very popular not only with the working class and the unemployed but with the middle class and even with some of the exploiting class. Later on in retrospect some of these people who liked him and profited by his actions and his decisions, hated him for these same actions. Because they wanted to get back to the good old days when industry was free to do what it pleased regardless of the consequences.

One of the results of this Roosevelt dream was a new art school in Buffalo, not connected with the museum, not a school for wealthy children but a school for anybody who wanted to study art. The school was on the second floor of a downtown building, a very adequate place. I found out about this very quickly and being out of work I registered with the school. I chose the class in sculpture because somehow during my youth and during all my artistic adventures I decided I’d rather do sculpture than painting or colour work. I believed that sculpture was more achieved, more definite, more of a statement than painting. I was wrong and today I don’t believe that at all. So we had modelling stands and portrait models and figure models. Some for a few days and some for extended periods; a life figure could sit there three or four weeks. We worked in clay and learnt a great deal about armatures and clay and keeping clay in working condition and so on. The students became friends and we were very interested, we were all interested and we got more interested as time went on and we exchanged ideas with each other. At any rate I had some of these friends for all of my life, all of their lives.

We were a group of six or eight serious artists and we were in touch with a lovely elderly woman who said: “I have a studio of my brother’s that is not used and if you boys want to come up and make use of that studio, I will give you the key.” It was like heaven you know. She gave us a vast cleaned out room in Buffalo at the edge of the down-town district. She was very kind. So we did some work and a lot of talking there. I found out that in art you learn more from experience and from your fellow artists than you do from teachers or books.

Chapter 4... Unemployment, hitchhiking to Florida and back

At a certain point, I had no job and I felt I could do something to at least help my family because I’d always given money from my paycheck to my parents and I figured that they missed this. I decided to go on the bum, to go on vagabondage, picking fruit in the south. It was also coming on to winter and I thought I’d get a job picking oranges in the south and stay down there for the winter and if I made any money I could send a little gift home. So I left and I went on vagabondage, hitch-hiking. I thought it was possible to get nice rides and meet people and so on. But it was an introduction to all kinds of gangsters, perverts, and dangerous characters, but it was very good education. I went to Florida. On the way down, I stopped and visited Washington. I went to the State of Virginia. My father was a great student of the American Revolution and one of his favourite figures was Thomas Jefferson, a Virginian, so I had a sentimental journey there too. Coming into Florida from Alabama, I got a lift from some young men in a large open car with the back down. . It was pretty full but there was room for me. They were nice, of good-fellowship and pleasant, and as we were going along I guessed that they had stolen that car and that they were on the bum like me. In the evening they went carefully up and down the streets of a town. I didn’t know what they were looking for. They were talking to each other there in the front and I was in the back, I didn’t hear. So they finally found what they were looking for. They found a car and they got a rubber tube and opened up the gas and stole it from this big car and filled up their tank. They did this two or three times. I was part of a travelling gang. I was with them all the way through Florida and we slept in the side roads, somewhere. Then I went to Palm Beach, Florida. It’s a town of exclusively millionaires who are on one side of the main highway running through the town. They are on the sea-side and the other people are on the other side of the highway. In Long Beach, I left that group of gangsters in the big touring car. They went on and I stayed in Palm Beach. I went to an open air vegetable market and asked for a job. I met the boss and he looked me over and he said: “You talk to that man over there and he will put you to work”. So I went to talk to a young man there. And he told me: “Look, that boss of ours, he doesn’t like to pay real salaries, he likes to pay the minimum. He hates to pay more. I know you have to have money to live on so you will be paid a certain amount by the boss. You can just put a little money in your pocket from sales you make. Keep that minimum and just get what you think is an honest salary”. So I did like everybody else. And everybody was content. It was a very busy market. And really a lot of the customers tipped you for bringing the vegetables out to their car so there was some legitimacy.

I looked for a room right away and I went down the street there and saw a sign on a house saying ‘Room for rent’. So I knocked at the door and a lady came. She said: “Well, it’s not really a room, but I’ll show you it”. She had taken her chicken coop and turned it into a little room. It was airy. It was just a shelter really and it was lined with mosquito netting and a mosquito net door. It was very clean and newly painted and the floor was covered with a piece of linoleum and a carpet and so on. So it was quite pleasant and the bed was satisfactory. I stayed there for several weeks.

Of course the problem was eating. I didn’t earn enough money to eat in restaurants because the restaurants were very scarce and rather expensive there. So some voice in the fruit stand said: “Go out to casino, a gambling casino, and go around to the back door and you will see a little table there. And you knock at the back door and they will bring you something to eat”. So I went to the gambling casino and somebody said: “Yes, you just sit there. This is a good hour. We have gamblers that nervously order food but never touch it. It’s a shame to throw it away, it’s perfectly good. If it has been messed up and so on, we wouldn’t give it to you”. So I ate very well cooked food there. And I could come any time I wanted in the late afternoon when business started there. In the middle of the town, available to both the rich and the poor was a little park. In the park there were shuffle board courts like on a ship. It was a meeting ground of the very wealthy and the poor. I was playing shuffleboard now and then with very well dressed, well-heeled, obviously very wealthy people. They were very kind and very nice.

They were mostly old retired millionaires, beyond the age of making money who had reverted to a very simple life. It was a very interesting combination: an outcast associating with these very wealthy people. Miami was a big city. I met another gang that included one of the people I knew from the previous ride. And I remember spending some time with a group of young transients. Sometimes these boys were really high on hashish. I was innocent. I knew hashish in Buffalo. It was considered a sure way of failure so I was not at all tempted. I was with these guys and they seemed so strange and fantastic to a person who wasn’t smoking this stuff. I remember this boy holding my shoulder to go down a curb because he was afraid it was too deep.

After, I came back to my fruit stall for a while. Then I went north because I got a letter from my mother saying that she would like to see me back and ”am I all right?” She was missing me. My paternal grandmother was living with us, and she also missed me and so I decided to go home. I had ideas of picking fruit and really you had to know somebody to get the job. So then I left Palm Beach and I started on the track home.

There were so many young people on the roads, hitch-hiking like me, men and boys that the government turned old Army bases into transient camps. They opened the thing and you ate at the government expenses. And so after a lot of dubious and painful passage sometimes you could get into a place like that, it was like heaven. You had a bed for yourself. You had a locker to put your things. I was arrested by the police as a vagrant in Jacksonville. They got me into the police station and they said: “Now you have a choice, you can either go to prison camp or you can go to this government camp. Which do you wish?” “Well, the government camp”. They said that because the prison camp was notorious for punishing convicts by putting them in a little outhouse, a wooden house with the sun beating on it leaving them there for ages. Some of the prisoners died in there. I can’t remember the name of that camp, Sunbeam camp? Maybe...

I was in the government camp and we had voluntary work and you could work in the morning or the afternoon, cleaning or sweeping. They were making a road through the everglades and I got a job as assistant to the architect who was laying out this road. He was a specialist and had worked on the railroad routing rails for trains. He had been one of the architects of a completely new railroad center in Cleveland, Ohio, and he was out of work.

At any rate I started coming back home. I started hitch-hiking and I was near the rail-road line. And I met some guys and they said: “Take a train if you are going back to Buffalo. You’ve got a train here; it will take you to Cleveland and then you gain a lot of time”. I went with them and they went off on a train. I wasn’t ready and so I wanted to see how they got on the train. I didn’t look carefully enough. It’s quite a trick getting on a rolling train even though it’s going rather slow. You think it’s going slow but once you get hold at the iron ladder that goes up on the side, you have to hang on very tight. There is a ladder on the front and the back of some cars. I made the terrible mistake of getting on the back ladder instead of on the front ladder. On the front ladder you swing with the motion of the car and you have to mount the ladder at the same time.

On the back ladder, you swing round the corner of the car and that’s liable to break your hold and cast you off. And it’s liable to cast you in between the two cars right in the wheels. So I did that. I did the wrong thing. Luckily I landed not in between but I hit hard on broken stones, on gravel of the railroad line… Not really gravel but broken rock. There was a viaduct there and these guys who had seen me fall came, picked me up very carefully and brought me in under this viaduct in a shelter. They found a place for me and got some cardboard, laid me down and took care of me as if they were my family…Very, very nice. For two days I couldn’t move at all. And people brought me things to eat: bread, cheese and things to drink. Then there was a big black fellow, that came and he offered me cigarettes. I was smoking rolled cigarettes. He offered me cigarettes and I rolled one. And he said: “Roll one for me, will you! I can’t roll cigarettes. My fingers are too big”. So I rolled a cigarette for him and he brought me paper and tobacco and chocolate bars and so on. And I rolled him cigarettes. He was very contented. He said: “Ah, that’s very good. I love to smoke”.

So, I knew that my elder brother Fred was getting married. I knew the date, and this fall of mine made it very difficult for me to move. So finally I recovered a little bit and I got out on the highway and bummed a ride towards Buffalo. I stopped on the way in a transient camp to rest for a day there. That was a main highway. The automobiles sometimes were very terrible, very rude. They would do a trick. You would be standing there with your thumb out and they would come up and slow down and you would think they were going to take you and then they would go off. It was really terrible how some people can become sadistic, you know. At any rate, I got to a little outskirt town of Buffalo and I knew somebody in that town. I knew them through my elder brother. I knew the address having been there. I had to walk a great deal. I came to their house and I knocked on the door. His wife came to the door and I collapsed. She knew who I was and so they got me inside.

And I woke up on a couch there and they took care of me for a day or so. Then they took me to Buffalo in their car. I got to Buffalo the day before the marriage. And I phoned my brother telling him that I was coming. I had to go with him to a place where they rented out suits. My brother was getting married in morning suit with tails and striped pants and a black coat. So from being a bum on the highway I was suddenly dressed up. This was typically my brother to get that kind of a fancy dress marriage.

Fred was a school teacher. He went to the State Teachers College in Buffalo and then had a job in the New York City area. And he ended up on Long Island teaching and finally became a director of a school and administrator for the town. He was a devoted worker.

Chapter 5... Art school

When I arrived in Buffalo, my grandmother had just died. She had died while I was on the way and was buried. She was 97 and really nobody paid any attention to her except me. My mother had animosity towards her because she had already a husband and three growing boys to cook for and another person in the house was difficult. But I liked my grandmother because she was an avid newspaper reader. I don’t know how she saw because she had glasses on that were sometimes double field glasses. She ploughed through two newspapers every day. And she knew everything down to the local gossip and the local politics and so on. And she had always done this. When I was in seventh grade or so and I was studying American history, I talked to her about Lincoln. And she got out clippings of newspapers of the death of Lincoln and obituaries and so on in the local papers. She had been a fan of Lincoln and that endeared her to me. And she was in the crowd when the coffin with the body of Lincoln was in the train all over the US. So at any rate I continued my art school and really there we formed a group of art students who were rather serious. And we worked together and talked a great deal about art. I found out really that much I learned about art, I learned from my fellow students. We got curious and we looked things up and so on. For example, I was a student of a German emigrant sculptor. He was a rather nice man, not interesting as an artist at all but with certain basic hints of how to handle clay and certain technical information. There were students who were more or less serious like our little group there. There were also people who came to pass their time playing at being artists. They were interesting too. And there were people sent by their psychiatrists to help them because they believed that art was good for them. That worked very well. So in several cases, many of these people were miraculously integrated. I remember people who were very nice. All my life, now and then, I have helped people teaching them how to model. It has always been very interesting and very pleasurable to see somebody wake up. I had an elderly man, coming to see me in France and he paid me something for the use of the studio and for my help. He was very nice. He had even a tiny bit of talent and was serious. He did some rather nice things. It was a pleasure to have that experience.

In the course of events we had exhibitions. I started doing some individual work which wasn’t in the school curriculum. And I had some success. I had people who liked my work. I showed in the area, had an exhibit in the museum and I got a prize from the Chellenor Foundation. It was a small amount of money, 500 dollars, but very pleasant for me. And later on I met Mr. Chellenor. He was a very interesting man. He was the son of the man who had established the prize.

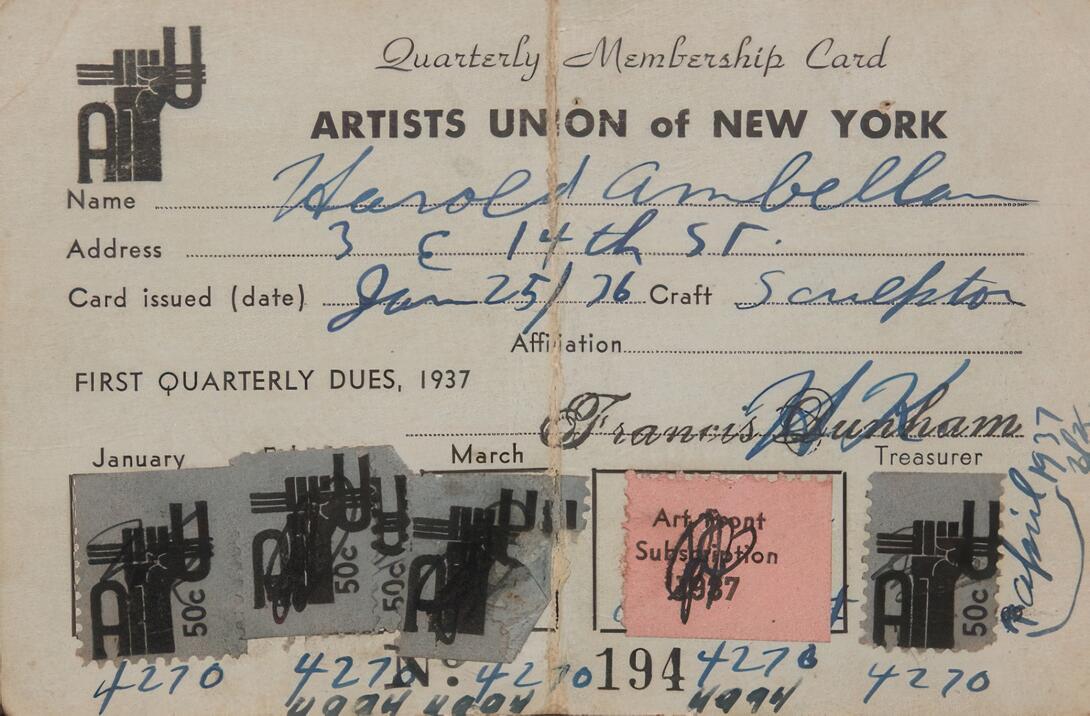

Chapter 6... New York: Artists Union, Sculptor's Guild

So I decided to go to New York. Buffalo was a town with no galleries. No visible signs of interest in art. So I went to the big city, New York. I had in my pocket a letter addressed to Gaston Lachaise, a French artist who came to America and made his reputation in the New York area. A very fine man, a very fine artist. A friend of Mr Chellenor who met me gave me this letter and said: “I know Gaston Lachaise and if he needs you, he will hire you”.

I went to New York. I didn’t go to see Gaston Lachaise right away because I wanted to get a little settled first. So I got a room and I even got a job. I got a job in a restaurant chain where they made all the food.

I was 22 or 21. I can’t tell you exactly because it’s all jumbled up in between graduation from high School and this job. In a few years, a lot of different things happened. I got to New York in 1932. I graduated in 1929, so that’s three years. I might be a little wrong. I got this room in 9th Avenue. I got the job first and then the room very close to the job. I started night shift going to work at one o’clock and getting out at eight or nine o’clock in the morning, having two meals at the job. It was work that didn’t pay very much but you had all your food. Then I was working there and I got shifted around from one department to another from the bread bakery to the pie bakery to the handling to the oven man. I did all sorts of things. One of my jobs was now and then to unload flour. They had a delivery of flour once or twice a week and I’d be called to help. Two of us would have to unload these trucks onto trolleys and other teams would take them away: truckloads of sacks of 200 pounds.

I had a fellow worker there who I liked very much and we formed a team because we had to do it two at a time to really load these trolleys fast. You had to do it fast because you had to clear that platform for the next truck, you know. There was a series of trucks that came. You couldn’t have the trucks standing out on the street. So I worked with this very nice guy several times and one day we were working together they asked me to do something else, I forget what. And that day there was rain and he slipped from the iron platform. And they had to take him to the hospital because he had developed a hernia, I went to see him in the wonderful New York hospital, which had the highest standards. Anybody could go in there. While he was in hospital, we made a collection for him to have some money for when he got out of hospital, because he

had no insurance. At that time there was no compensation. There was no way for him to get any money from this company and they didn’t offer anything, not a penny. I think that’s cruel. I saw him a little bit after that. He couldn’t work anymore.

Meanwhile I went to the art school in New York, which is called the Art Students League and it was established years ago. It’s a school entirely run by the students. The professors are chosen by the students and the courses and instruction also. So it’s called the Art Students League.

I went to the professor of sculpture, Mr William Zorach and I showed him my photos. He said: “No question about it. You come and work here whatever you want to do”. So I went there. I was working nights. I spent several hours there. I did nothing, really, except go to that school and go to work and cram in some sleep. And one day I was reading the New York newspaper and I read about the death of the addressee of my letter, Gaston Lachaise. Later on, I met a young man that had been what I would have liked to have been, his assistant. So he told me a little bit about him. And I regretted that I hadn’t met this great man. His work is now in the New York Metropolitan Museum, on the roof. They have a terrace on the roof with marvellous sculpture, very nice.

While I was in the art school, a young girl student, very charming and very nice, told me: “Well, you’re going to join the union”. I said: “What union?” She said: “The Artist Union”. I said: “I don’t know”. She said: “Oh yes. You come along with me and I’ll show you”. She was a red hot unionist, I went to a meeting and I found the whole union in ebullience: they were protesting against a New York Project where the artists were employed to wash and reframe paintings in the City Hall and do errands for the museum and wash the public monuments in the parks and so on. They demanded to open up a project for creative art. Art by artists. So in order to do this they said we were going to meet Mrs Audrey McMahon who was the director of the project. We were going to meet Mrs McMahon and we were going to state our whole case to her. We needed a good following of people to impress her. So we had a meeting arranged with her and showed up with 219 odd members and she said: “You don’t have to be that many, I could just talk to two or three of you, that’s all. I’m all in favour of your ideas, but I have no budget now. I have to present this to my superiors.” The organisers of our union said: “We’ll wait here until you talk to them”. So we sat down.

This was the first sit-in (in December 1936) that stimulated the same action in all different parts of the labour movement. This was the first sit-in with a group of art students. There were 219 of us. Later it became quite an honour to be one of the 219. So we were there. The police came and said: “You must vacate these offices immediately”. So we sat down on the floor and they had to pick us up, one at a time and escort us out to police vehicles and carry us off to the police station. We said to each other: “We won’t give our real names. We’ll give the names of famous artists”. So we gave the names ‘Leonard da Vinci’ and ‘Michelangelo’ and so on. And the newspapers wrote a wonderful story about the ‘great artists of the world were in New York and being taken to the police station’. It was funny. We got very favourable support from the press. It was obvious you don’t have artists working at just washing and polishing. You have them making art. It was very interesting.

This artist union later became affiliated with the labour movement in America. CIO. Of course we were attacked for being leftist. We ended up having a great deal more members. Following this, the writers, the actors, all the cultural workers became organised even the entertainers, the musicians.

It was a wonderful period. They took over a theatre that had been closed because it was the Depression. The prices of tickets were reduced, so you could go to see a play for the same price as an ordinary movie: 25 cents. I remember seeing Orson Wells doing Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar for 25 cents. I went on one of the last days and Orson Wells came out on the stage after the play. He said: “We, this same group, are now going to rehearse the next play which is to start next week. If you want to stay for this rehearsal, come back in 25 minutes. You will have time to go out and have something to eat”. So we saw the other play which was called the “Shoemakers Holiday”, I don’t remember who wrote it but it’s a very good play, too. We had the best musicians, the best concerts. It was a very creative and wonderful period. Of course it was hated by some people even though they benefited from it. The wealthy people had a natural distrust of anything that was social or socialized. But it was a fantastic period and it was due to the wonderful cooperation of the President Roosevelt, and the wonderful vision he had. He said: “It is absolutely impossible to have a country where people are unemployed. I will do everything to create employment. If we have to spend our last money, it’s well spent”. A wonderful man. He is the greatest political thinker since Solon, the Greek. Just imagine, he started a camp where untrained boys, young men coming out of school, could get paid for planting trees. It made a wealth for the nation which was fabulous. It required lots of money and great decisions.

So I found myself involved in this new project. I was assigned to a group of people making cement castings of animals for children’s playgrounds. The children would crawl over the animals. And so that was my assignment, not very interesting, but I said: “It’s not going to last for ever and I’ll get something else to do later on”.

So I had this job and then I rented an empty loft, in lower New York. In a street with lofts that had been all sorts of things before, small businesses like the clothing business and so on, with nothing but walls and the floor.

I was fascinated with New York and I started doing a sort of survey of lower New York, and so in no time at all I was drinking too much. I was staying up late at night and sleeping almost on the job. Finally there was an assistant supervisor of this sculpture project I was on and his name was Maximilian Machovsky.

He came on the job and talked to me. He said: “What’s the matter with you? You’re looking so dopy here.” He had talked to the other people on the job before and they were all a little bit worried about me and I said: “I’m all right”. He just nagged me saying: “Look, first of all, you’ve got to clean up that cough you’ve got. I want you to go hospital and get that cough examined”. He said: “You take off tomorrow and go to hospital and see so-and-so…” So I did that and he followed me up the next day. He came to see me and didn’t find me there but he found me in the street. He said: “Look, your studio is there. Let me see your studio!” So I took him up to my studio. He said: “This is not a studio. This is absolutely the end of the world. You got to get out of here.” So he found me a studio, that he knew was empty, a real art studio. He insisted in helping me personally to move, and settle there. He followed me up for a week and I responded very well because I was being a bit experimental there. I really wasn’t an alcoholic. But, I could have become an alcoholic. At any rate I think of Max Machovsky with a great deal of pleasure; a red haired Polish Jew “a real Pole.”

So things went on in the artist union. We had a section of sculptors and became busy with that and then we had official shows in government sponsored galleries. But we also had shows of our own, so we had quite a busy schedule. I was working and making things and enjoying myself. I had some success. I was president of a new group of sculptors called ‘the Sculptors Guild’. It was at first called something else. And they were a very nice group of people. Of course, the unions were undeniably part of the Left.

The following years, from 1933 to 1937, I was in this organisation and this work. At a certain point we had projects: we made sculptures for government buildings. I made a sculpture for a Post Office in New Jersey. Then, with another sculptor, we made four grand figures on the walls of a housing project. It was in a black area so we did things that could be interpreted as black too and so on. It was a housing project where all the doorways had sculpture models on each side, small sculptures. Four or five buildings had large implants of sculpture on the walls. It was quite a nice thing and it got some publicity.

Then partly because I came from Buffalo, I was asked to make some sketches of a new bridge crossing the river from Buffalo to Canada called the Peace Bridge because it was between two peaceful, neighbouring nations. I made some studies and the architect was very much on my side but they didn’t want the project.

So, during that period I exhibited in Philadelphia, in Boston and in several other places.. I had as much of a reputation you can get in America, but there is very, very little chance of making a living with sculpture anyway. You can successfully show things but it never really pays; Basically they think art is a hobby and you are getting pleasure out of it and that is enough. And that is the way people, many people, talk about art. You can’t make a living out of it unless you have money behind you or if you have an unbeatable ego and are ready to push. Even then I have known people that have had very great difficulties even though they spent every day trying to succeed.

Now at the end of that period, the war in Europe had started and production, business and industry had picked up in America. So there were a lot of new war contracts and a lot of employment created. So this wonderful situation was abandoned, that political marvel that led you to believe that we were on the road to democracy, because there were so many people converted to a new outlook on life. I remember I was on a neighbourhood committee looking for people who were suffering from malnutrition and abandonment. So there was a house survey, we had a door to door survey, going with a couple, a man and a woman. This was started by this union. We belonged to something called the Workers Alliance. We discovered that there were people who were living in respectable areas, in luxurious apartments, who were at their very last penny, starving to death. They owned an apartment but they no longer had any money coming in and they were too old and just dying of starvation. I remember we found a woman, an elderly woman. So we went to this woman and talked to her. We said, “Well, you know the government has funds for people like you. Just come and apply for that, we can come with you.” She said: “Oh no, I’d never do that, I’d never do that, I’d rather die.” I said: “Oh no, you wouldn’t rather die, you’re too nice to die.” I remember that woman. We finally got her to apply and she became a member of this Workers Alliance.

Chapter 7... New York: end of the New Deal, tile business

And so came the end of the art project because normal business started. War makes money and money makes jobs possible. The only time capitalistic society really works is preparing or recovering from a war. So I lost my job and my project was cancelled. I had foreseen this and I had an idea. I had a friend, an artist who was investigating silk screen printing. Silk-screen printing at that time had been used for theatre, for automobile advertising. Large posters were considered a cheap substitute for lithography. But lithography was much more varied and more complete. I had done a little bit of ceramics and I thought: “That’s an interesting thing”. So I decided I’d make ceramic tiles with this method instead of brushing them individually. I made some samples of this new technique and I had some encouraging results.

So when the project ended and I was out of work, I took these tiles around to a man who made iron tables, iron garden furniture. Some tables had tiles I had seen and liked very much. I knew where his shop and his little factory was. So I took some of my tiles and brought them round to him. He said: “My God, it’s just what I’m looking for. You know I can’t get any more Spanish or Italian tiles and those were the only tiles for my business. How much do you want for them?” I said: “I don’t know.” And he said: “Well, you figure out how much you want! How do you stand for money?” And I said: “I have to go easy.” He said: “If I give you a thousand dollars, will you be able to put this thing on?” And I said: “Yes”. A thousand dollars was quite a piece of money at that time. So I started to do that and I had a business then that lasted fifteen years. At the same time I met a woman, Elisabeth, that I liked very much and she wanted to help me. Finally we got married and we lived with each other during that period. She was very apt as the manager of such a business. We had five to eight and later on about eight or ten people working there. We started in the New York wharf, in the New York business area where we could print these things but we didn’t have a kiln. And you have to fire these things in a kiln so we started there and made a deal with a place in New Jersey to do the firing. Finally a great deal of our effort went into transporting these things two ways. So we took a new place with a little room and bought a large kiln and that worked like a charm for fifteen years.

By this time, the Spanish tiles came back again and we had built up a certain clientele for a different kind of design, a little less Spanish. We did all sorts of things: some were floral designs, some were pictorial. We had a tile with a poem about coffee drinking. They were often inspired by the civilisation of New England. At any rate, we had a rather nice collection. It wasn’t art but it wasn’t the worst kind of commercial art and we had a lot of very happy - I don’t know how efficient - but very happy workers there because we took especially people that needed a job, or needed support, or friendship. My wife Elisabeth was very social and attracted these people who came to her for help. The tiles were made with a squeegee in your hand and a moveable platform. One person would put the tile on the platform and picked up the squeegee and did a stroke. The other person took the tile away and brought another one so it went pretty fast. One every two seconds perhaps for one colour. And there were four or five colours.

I had a friend, Ben Karp, who came in and wanted to work. You could hardly get him away from the machine, which was a sort of a wooden contraption. Ben Karp was a very fine person, our teacher, an innovator of techniques for teaching. He was an artist himself. His wife, Vivian Fine, was a pianist who specialised in things that were terribly difficult and terribly powerful, disturbing and dramatic. She became one of the finest composers of America. So he was the husband of a woman who achieved greatness in her lifetime. Very nice woman.

Chapter 8... New York: Ernie Meyer, Greenwich Village

I had many friends: Ernie Meyer was one of my greatest friends in America. He was a reporter for the New York Post. He was not only a reporter, he wrote a daily column on the front page called ‘As the crow flies’ meaning ‘straight’. A charming man and a dedicated left-wing figure. I met him through other friends of mine and I was invited to his round table. He held a round table once a week where he paid all the drinks and all the bills and only invited people he wanted to see and talk to. It was a very interesting group because it was not at all definable politically or socially. There were all sorts of people there with all kinds of approaches and ideas and so on. He said, “If I only chose people with my ideas, I’d get nowhere at all. I like to hear other people, other people’s idea; they might be better than mine.” A very, very, very fine man. He was Milwaukee born of a German speaking community there that were mostly left-wing, anarchists. The anarchists that I’ve met in my life have been the most gentle people in the world. We used to meet in New York. The jumble shop was on Eighth Street, the main street of Greenwich Village. It was a real ‘village’, with a kind of social ‘camaraderie’ which was remarkable for a big city. Everybody gravitated there for interesting things, for seeing things, for the few galleries that were down there, for the Whitney museum. It was the cultural center of Manhattan.

I also used to come to Ernie Meyer’s house and sit with him. He loved having company and he was not very physically fit. I enjoyed visiting him, I think he enjoyed having me. There was a difference of twenty years in between us. He was just as interesting as my younger friends, much more really.

When he died, there was no funeral. He was buried by his son, the only witness to his funeral, it was a simple affair but he left a fund for having, one month after his death, a ‘soirée’ Ernie Meyer. He had already rented a room, the second floor of a restaurant there. So the whole evening was devoted to his friends and there were people that made up speeches and poems about Ernie and recited them and told stories about him and it was the most perfect funeral I’ve ever been to. It was not a funeral. That was typical Ernest Meyer. He was one of my very best friends.

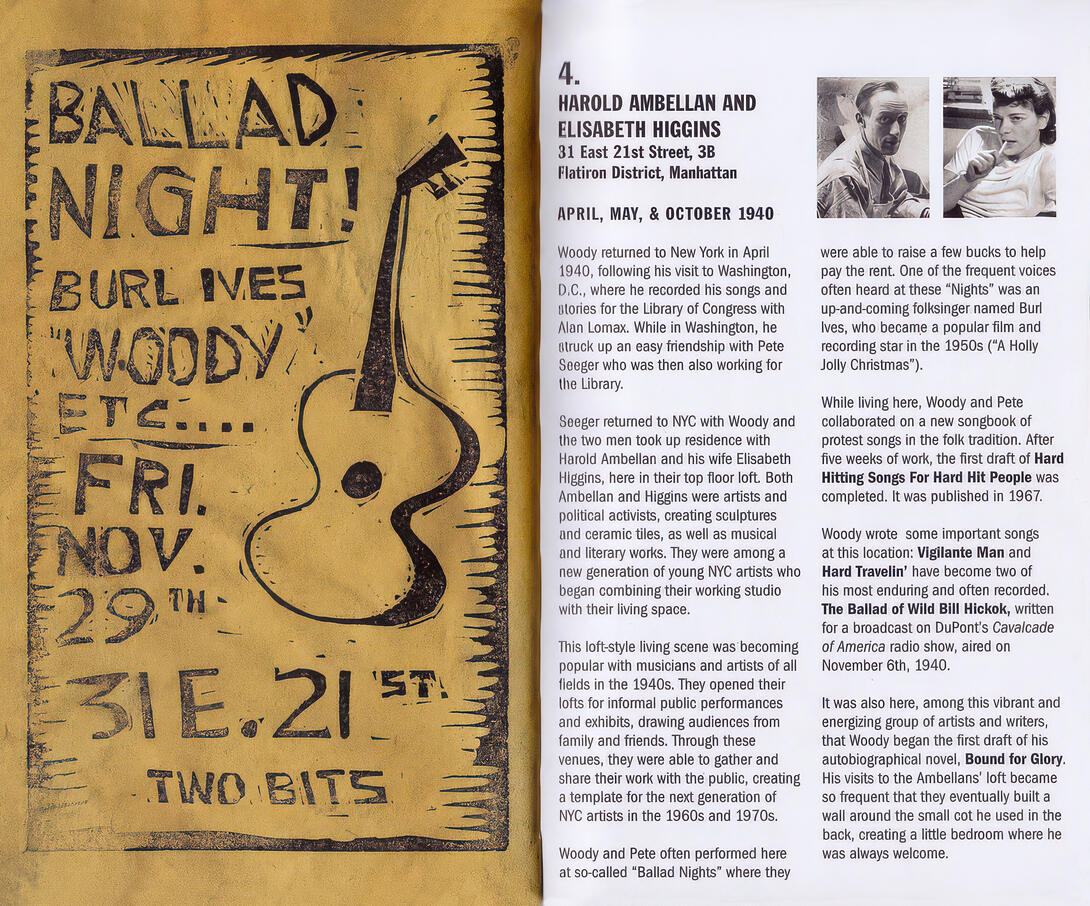

Another thing that is interesting to recount was that my studio on 31 East 21st Street was on the top floor of an old brown stone building that was at one time the single home of a wealthy bourgeois family with four floors with a lot of bedrooms and servants quarters. I had it for 20 dollars a month. 20 dollars was a very low price but quite common. I bought second-hand linoleum and covered the old floor which was very, very worn and bumpy really with probably half a century or a century of workmans’ shoes use.

Below me was a woman and her husband who were sort of theater amateurs. They had theatrical or musical ‘soirées’ from time to time and they invited me as a neighbour to come and see. They were very nice neighbours. The first floor was taken by the ‘Photo League of New York.’ It was a league of professional photographers for the whole country. Every photographer of importance belonged to that league. So it was through it that I met a marvellous photographer. I can’t think of his name because I have a sudden lapse of memory for names that I should remember. I met also Weegee who has recently become sort of a figure of importance. He liked the accidents of the enlarging machine and the accidents of acids and chemicals on photographs, as well as exaggerations. He was a police photographer. And he did all kinds of lurid photographs. And he was out all night of course. He was a night walker of New York. He took pictures of the opening of the New York Opera. Of people getting out of their cars and taxi cabs and getting in again later, leaving tired and their make-up gone. They showed these very, very rich families the highest ranking social families in America, at their very, very worst. And at the same time with a certain human sympathy. With some kind of a feeling of ‘well now, can’t be any worse than that’. So these photographs appeared in the big magazines in large. So he was considered a very special photographer.

I also knew a young photographer there who told me he was going out to photograph seagulls on Long Island. That he’d found a place where there were the most seagulls nesting and he was going to spend a week out there. So I saw him just before he left. And I saw him when he came back. I met him in the laboratory downstairs where he was developing his pictures. And I saw these photographs. This young man really became a bird. He became a friend of these seagulls and he had little seagulls on his hand and seagulls all over him, walking over his feet, stepping over his feet. Marvellous young man.

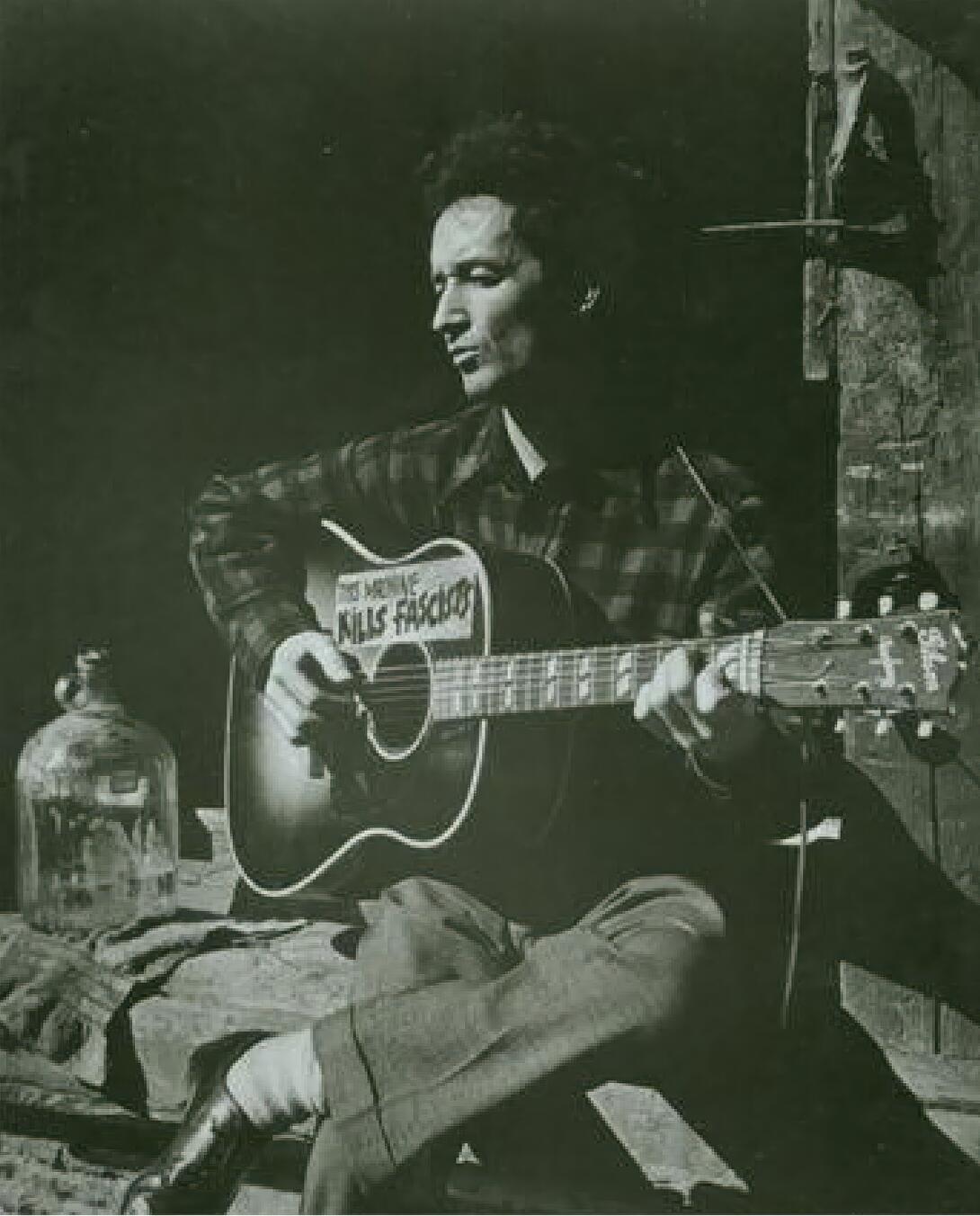

The other thing I wanted to bring up was theatre in New York. I think when I first came to New York, they played ‘Tobacco Road’ written by Erskine Coldwell. It was playing for something like its 200th performance and it went on for several years more. The leading figure was the man who played the father of this poor Tobacco Road family. It was played by Will Gear whom I met and I liked, and he invited me to come… He said, “Anytime you’re up town, drop in the theatre and say ‘hello’.” So I did that and it was a pleasure to watch him prepare himself for this role. He said: “This role depends on the clothing I’m wearing there and the dust in these clothes. If I create enough dust, I know that I can act it very well. Because I believe what I see.” Very charming man. I met him through Woody Guthrie.

Chapter 9… Music, Woody Guthrie, jazz

In recording all these things, I neglected something that was very important in my life – my musical side. I really owe quite a bit to my High School. I had several very good teachers there. One morning a week we had some lecturer or something interesting or something made by the students, some play. And one day I went there and they had Carl Sandburg, a poet of the mid- West. He was a poet, a very simple poet of simple things and simple people and very profound. A very, very lovely man. He was a Swede I think and living in Chicago or Milwaukee, one of the mid-western towns. And he had written several books of poetry that were quite popular in America. He came and recited his poems and we were all very pleased because he was quite well known and when he finished reading several poems, he went off stage and brought his guitar on the stage. He said: “This is my real interest at the moment, I’m finding these lovely folk songs, American folk songs which are fine poetry and very expressive.” So he sang several songs, prisoner songs and escaping prisoner songs and farmer songs. Very well chosen, funny things and interesting things. That gave me an interest for folk music for the rest of my life.

So when I grew a little older I had a ukulele, that was my first instrument. I played it when I was eight or nine years old. As a matter of fact, the first ukulele was made with a cigar box, a home- made instrument. Then I got a present of an ukulele from my father and mother. I spent hours playing and singing and making up songs. When I grew older, in my last years in High School, I had a real guitar but it was a five string guitar and very hard guitar because they usually have six strings. I played that also by ear, simple chords that you learn, and quite repetitive. I was in great demand at family reunions and birthdays. We were a great family for all getting together for these simple birthdays and confirmations. I would accompany singers. They all sang. I played these songs very well with simple chords and I sang with them and knew all the words. I knew all the songs of my generation and also of my father’s and mother’s generation. I knew all the popular music of the eighteen eighties, eighteen nineties.

When I came to New York I was busy with other things and finally I bought another guitar. I played a little bit. Elizabeth found that there was a singer from the mid-West, from Oklahoma, who was in New York and he was coming somewhere to sing. There I heard Woody Guthrie and I was really captivated by his original folk music. I remember being in a small gathering in a small room, a couple of dozen people listening to his dustbowl blues. And his songs made up about the

dustbowl and the poor people being driven out of their homes by the dust and going to California, hoping to find work picking oranges and their bitter surprise to find there were thousands and thousands of such people fleeing from the dust bowl and there was no work for them at all. I had made this friend Woody Guthrie and I invited him round and accompanied him. We became very good friends. Finally at one point he needed a room and I had a large studio at the time with a little room in the back. A little room all partitioned off. The former occupant had a place to sleep. It was a business but he had a little corner to sleep in and to rest. Woody Guthrie for several years was a member of my family and I invited people to hear him play. Woody Guthrie was a very simple person who had absolute judgment of what is right and what is good and what is wrong. He had this disease that causes mental break-down at the age of thirty or thirty-five. And before that you are perfectly normal. So I was with him one evening and we were coming down the street and he got talking and I said: “What is he talking about?” He was angry and he came to a store with a little show window in front, and to emphasize what he said, he hit that glass with his fist and broke the glass and his fist started bleeding. So he immediately calmed down and said: “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.” He said: “I’m going the way my mother went.” From then on he was very careful but eventually he had to be taken care of. I saw him very little because it broke my heart to look at him. So I sent him messages via friends and I’d write him postcards and little notes and so on. A good man. That was in New York. He went to an institution in Jersey when he became ill. And there is a fund created by his ex-wife to fund for this disease.

Somebody gave me a couple of dozen folding chairs and I had sort of a folk music centre for all the lovers of this special kind of music in the New York area. I had all of the American folk singers, singers from the south, Aunt Molly Jackson... Leadbelly was another folk artist that I met. I met him before I knew Woody, before I met with Elizabeth. I was going out with a girl who was a home-relief investigator. She said one day: “I have on my case role a very interesting man, a black man who plays the guitar. His name is Leadbelly. So she invited him with his wife to her house to have dinner. They came very well dressed and very polite with his twelve string guitar in a case and I was late for that dinner party. I was late because I had taken a nap in the afternoon and slept too long. I was an hour late or half an hour late. So we had dinner and polite conversation and after dinner he got out his twelve string guitar from its case. And he said: “I’m going to play you a song about a young man who is so busy with his affairs that sometimes he is a little late.”

So he became a very good friend over the years, in fact he was a friend till the day he died. He started making records and did rehearsals in my place with some people accompanying him and with a group of singers. It was very, very pleasing. I had a very large loft and I loved to have this kind of contact.

I also knew a lot of jazz people more or less through him because he was also very popular with the jazz singers. He was doing a different kind of thing but they saw his value and they liked him very much as a person and as a singer. So I had a very nice friendship and also he had a very charming wife, just a loveable person. At a certain point he went to Europe and he sang in France. He had a concert in Paris. He had other concerts arranged. He couldn’t finish them. He became very, very ill and had to come back and went straight to hospital. I forget what the disease was but it was incurable. It was an incurable disease of the nerves, I forget which and he died. It was a very rich friendship and really a direct experience with a black person from the South. He was from Louisiana. He said: “I was in prison to fill the camp, to fill the prison camp. There was a white man shot and they arrested every black man in the whole town and put them in jail. And they charged them all with the same murder. I was one of those men. I was condemned for man slaughter of a man that I didn’t even ever know.” He was singing in prison. A singer was necessary for a work gang because he kept a rhythm for their work when they were chopping or when they were carrying rails. There were certain rhythms for certain works and he was an expert at that. And he made a record of these songs while he was in my studio. He did it with a group of singers called the ‘Golden Gate Boys’. And they were black singers from California. He said: “They had to learn how to sing like prisoners.” And he went over these things with them and finally they got the spirit of these songs. And they made a record that was really monumental, really fine. A fine work of art these work songs. I don’t have the record any more. I’ll have to find it.

So I picked up all these songs from everybody. I know hundreds and hundreds of songs that I learned over the years, that I have often sung for my friends and for organizations sometimes. In fact in New York I was singing so much that I had notices in the paper listing me as a singer. I said: “I’m not a singer, I’m an artist.”

In France I always sung. I sing even by myself a great deal. I enjoy singing so much. I’ve sung for the American library in Montpellier. I did a concert for them and it was very pleasant because I sing only in English. These songs are really only appreciated by people who understand English. But I sing now and then for French people and they enjoy it too. I made a couple of records not commercial at all, some records for these organisations. Lately my guitar developed an illness, doesn’t work and I haven’t gotten around to getting it fixed or getting another guitar because I have been too busy with other things. So my career in music has halted but I enjoy it very much. I enjoy serious classical music too. So that was a little insight into my musical career.

Chapter 10... Sailing